A letter, written by Sergeant David Denchfield of 610 (County of Chester) Squadron, is the heart of Westhampnett at War.

Denchfield describes life at Weshampnett and his crash and capture on 5 February 1941. The letter is too long to quote fully, but a few excerpts offer the atmosphere:

“I was on readiness, when mid-morning the Commanding Officer popped his head into ‘B’ flight to say ‘released from 13:00 to 9:00 tomorrow morning’. As we all gave vent to various sounds of appreciation, he then smiled and said ‘that’s after we get back from St.Omer. Take off at 12:00’.

***

There followed a fairly basic briefing. We would follow 302 to Rye, climb up through the 10/10th cloud to about 15, 000 ft and join up with the 7 other fighter squadrons, where we would be top but one (having Tangermere’s 65 above us). The whole shooting match would then escort 12 Blenheims to St Omer, where they would cause great alarm and despondency with their 250lb bombs.

***

We broke into brilliant sunshine and climbed to our angels 15, by which time we were orbiting Rye and waiting for the off. The strange thing was, I could see no aircraft above us. Weirdly the cloud over England ended at the coast in an almost vertical cliff edge, leaving the skies over the Channel and France completely cloudless. The Channel to the east looked ridiculously narrow and the skies over the snow clad French landscape were broodingly ominous. As usual, the sun glare out of the clear blue made looking to the southeast difficult. God only knows what nasties were moving into its hidey-hole and as we circled Rye for a good 5 minutes at least, we certainly gave them plenty of time to get ready for us. I guess, like me, that the others had their gun sights switched ‘on’, their gun firing buttons turned to ‘fire’ and their hoods slid back for better visibility…and I bet they were sweating cobs too.”

The story continues with an attack that riddles his Spitfire with bullets, mangling the port wingtip and draining the fuel tank. He drops to 6,000 feet, sees the Channel and watches the retreating Blenheims pass overhead, on their way home and “going like the Devil.” He realises that he won’t make it back to England and with the cockpit full of fuel, it’s impossible to put the plane down. He bales out, losing his boot in the process and ends up in a coverless field in France. Within moments, he is confronted by German officers:

“…as I stood up the one with the gun said ‘For you the war is over’ (and I thought they only said that in things like ‘Hotspur’ and ‘Magnet’. We live and learn.)

It was all very friendly and we walked as a small group down to the opening they’d come through…We got into the Ford V8 they’d arrived in and drove, perhaps 400 yard to where the remains of my poor ‘P’ were smoking.

…we drove to the airfield at St Omer [where] a load of about 12 Luftwaffe pilots came to attention in front of me and then saluted. Of course I had to reciprocate. At that time there was a fair degree of mutual respect between us, mirroring WWI.

Anyway, I was treated with extreme courtesy…I was introduced to the pilot who had shot me down, Major Oeseau, who became one of the top scoring pilots before losing his life in 1944. We spoke for a couple of minutes and then I signed his cigarette case for him to have engraved over.”

He then relates his transfer to a Polish POW camp for the remainder of the war and sadly recalls that of his immediate friends, none lasted past September 1941.

Denchfield himself survived. His family returns to France every year to visit the grave of his friend, Billy Raine, who was killed only 5 miles from where his own Spitfire went down.

The book includes a photo of Denchfield in 2009, neatly dressed in a cardigan, walking stick in hand, leaning on the wing of Goodwood’s Harvard. He looks quite tough and like a bit of a trouble maker- somebody’s slightly cantankerous grandfather.

After all that happened, not only does he willingly record it in a letter for publication but happily re-visits the airfield and gets back into a plane. I wonder what makes the difference between a war story that is re-told a thousand times and one that is never spoken.

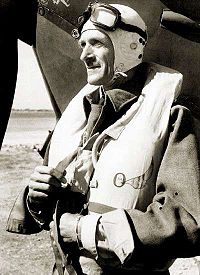

Marshal of the RAF, Lord Tedder, credited one man in particular for winning the Battle of Britain: Sir Keith Park.

Marshal of the RAF, Lord Tedder, credited one man in particular for winning the Battle of Britain: Sir Keith Park.